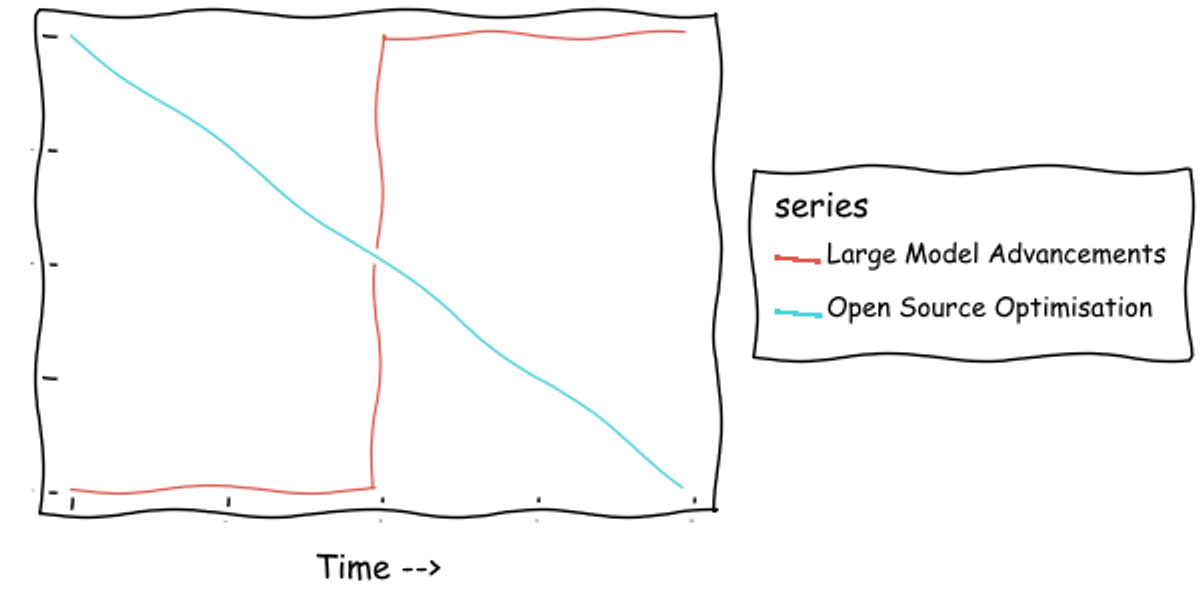

The GenAI field is going two ways at once now. One way is a trend that we have long seen and are at a position where we can take advantage. The other way is a potential step that could disrupt everything, again.

The Trend begins with the awesome and incredibly underrated memo “We have no moat, and neither does OpenAI” by an anonymous Googler. The concept of the “moat” is of a hard-to-assail incumbent advantage, such as by having masses of private data, infrastructure, or IP.

The blog argues that in the wake of the release of Llama, Meta’s open source LLM, the academic community has developed several techniques to shrink LLMs whilst maintaining their quality. It’s been phenomenally successful: you can now run models almost equivalent to the original ChatGPT on laptop hardware, for free and with minimal technical skills. Even on my four year old Macbook I can run and manipulate a beautiful menagerie of these models. This is the commoditisation of AI and it could kill OpenAI. Why would anyone pay OpenAI when they can run the same service in AWS or any other cloud provider, for less? Meta - who don't have an AI SaaS business of their own - are stoking this fire, actively trying to make open source AI the state of the art and default choice, to keep control of this technology out of the hands of competitors like Google.

OpenAI haven’t missed the threat. The new 4o-mini, being 60% cheaper and faster than 3.5 whilst still improving on quality, is keeping the shadows at bay for now. They are still on the Pareto front for cost and quality for all model sizes.

Yet the front moves ever forward. Whether OpenAI can keep up is one thing; whether businesses realise the implications is another.

The amount of data you can cost-effectively process with GenAI is growing. Costs have dropped tenfold or more for some tasks. It’s still more expensive than processing with the previous generation of AI, but we should anticipate it reaching parity in the foreseeable future. This means previously infeasible Big Data use cases are coming into view. While at the momentGenAI is most commonly used in small data domains, or at the end of a chain of data processing to enhance results for users, that could change. Large companies with big pockets will be able to do brutal things like chucking all their raw data into prompts rather than first refining it down to a manageable subset.

What then is the Step? At the time of writing, rumours abound about OpenAI’s next model, codenamed “Strawberry”. It is a leap forward, go the rumours, a major advance towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) i.e. an AI that really exceeds human intelligence across a broad range of tasks.

Obviously it’s not wise to put too much stock in rumours, but this is the goal OpenAI are aiming at. They are currently fundraising, seeking investment that would value the company at a staggering $150B. As amazing as OpenAI are, it’s also well-known that they are a money pit with enormous costs. A future where they are marginally ahead of competitors with a commoditised product doesn’t support a valuation like that. They are really asking investors to bet on their ability to deliver AGI. The fact that they’re asking now suggests to me that good progress has been made on the next generation, enough to share and excite investors.

What would that mean for the rest of us? It’s hard to say. Tasks that are out of reach for GenAI today, like writinga good story or doing scientific research, might be in scope. Which tasks we can’t say.

[Update: only a day after I first wrote this, OpenAI released a preview of their new model o1, which can handle PhD-level science and maths reasoning problems. Though the general release isn’t ready yet, it’s already possible to see that more old walls are going to fall to AI capabilities.]

How do you plan for that? And for the future steps that must surely be coming? If only I knew! But it is safe to say that if your current plans assume the medium to long term capabilities of GenAI won’t radically improve, they WILL be disrupted. I wouldn’t embark on any AI project with a delivery point of more than 6 months.

The interesting thing is that the Trend and the Step are in opposition. The Trend invites long term planning; the Step warns you to stay flexible and ready to adapt. It would most likely be a sawtooth pattern: a step comes, the technology trends smaller, and then a new step comes and it repeats again. But when should you adopt the new technology, and when should you ride the old one? It seems to me that the companies that can manage those tensions best will be the ones that succeed.